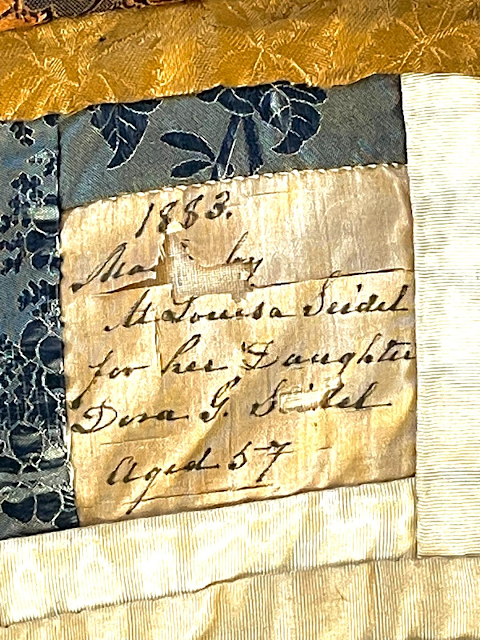

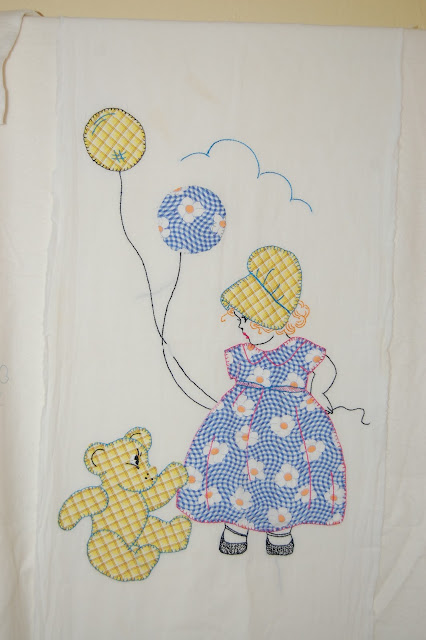

Andrew, great-grandson of Joseph Deibert (see here and here) emailed me again with a photograph of another quilt. This one was not made by Joseph but by his great grandmother and gifted to an aunt of Andrew's. It is made of silk:

At first I thought the backing was machine quilted and possibly purchased. I have a similar piece but the quilt pattern is different. After studying what I can see, I'm not sure:

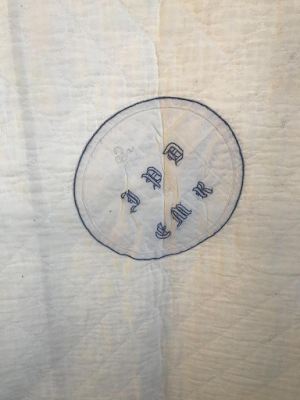

It's almost impossible to tell from photographs whether or not it was a machine quilted backing. The quilt is also inscribed and of course that makes it even more special:

This got me to thinking about machine quilting and I thought this week was as good as any to discuss what I know about the matter. I'm certainly not an expert and I've never found a definitive study on the subject.

But here is what I've learned just from reading newspapers.

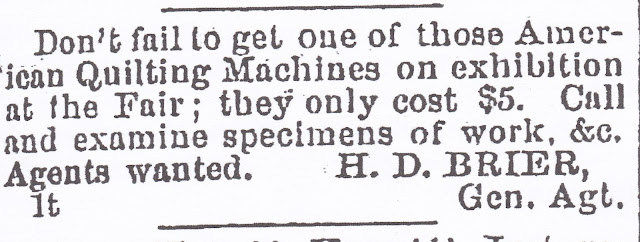

As early as 1872, I found evidence of a "quilting machine" in an ad from Montgomery Alabama:

In 1878, The York Quilting Factory (in York, PA) advertised that it:

"is doing a largely growing trade. These quilts are made of the neatest patterns of calico, lined with cotton batting, and are quilted on the large quilting machine run by steam power. Thus they are enabled to turn out quilts by the hundred daily, and can supply the world cheaply, and with the very best articles."

These quilts were made to be marketed in stores.

Insight into the machine quilting industry was provided a little more by an article published in Kansas in 1885. This article focused on machine made quilts produced in eastern Connecticut. Originally the companies hired farm women to hand quilt. The women were layed-off with the advent of machine quilting. It was simply more profitable to make quilts by machine. This article cited that 700,000 to 800,000 were produced in this part of Connecticut in just 1884; the quilts were sold throughout the United States.

1893 image of one of the Connecticut factories in New London, Connecticut.

The article cited that the quilts were not exported to Europe because "down coverlets, or those with wool filling, are used extensively on the Continent."

Originally traditional calico was purchased but that choice was discarded for plain cotton which was then printed: "originating their own designs for patterns and having the calico printed especially for their use." I have no idea if the fabric was pre-printed patchwork or what some call cheater cloth.

The fabric would then be assembled by machine and sewn on three sides to form a bag. The "bag" was then filled with batting and pressed down. "Three boys manage the rack, and so rapid are they that they readily fill seven hundred quilts daily."

After the fourth side was sewn closed, the pieces were taken to the quilting machines, tended by girls. The machine had a mechanism "that mechanically follows an arm running in a metallic guide to for the desired (quilting) pattern." The article does mention that the girls made two-and-one-half cents for each quilt, and forty quilts are considered an average day's work.

As if to apologize for the child labor: "Some of the girls make seven dollars a week. The work requires very little exercise of either strength or attention. It is a trifle oily, but is above the average of factory occupations in health and cleanliness."

It is unknown how many days a week or how many hours the children worked a week.

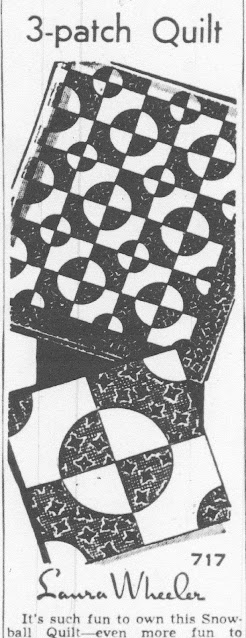

It only makes sense that quilted backings for crazy quilts and other silk decorative items were made and sold from machine quilting factories. Crazy quilts were meant to be decorative pieces that exhibited the woman's ability to embroider, manipulate fabric, and paint. Most of the makers were probably not that interested in actual quilting.